Guillermo Gaviria in Galtung’s 80th Anniversary Festschrift

Networkers SouthNorth and Pambazuka Press have released a provocative Festschrift (Experiments with Peace) to commemorate Johan Galtung’s 80th anniversary. The volume includes a chapter by CGNK founder and Governing Council Chair Glenn D. Paige exploring the nonkilling political leadership of Colombian Governor Guillermo Gaviria Correa (“Political Leadership, Nonviolence and Love: Governor Guillermo Gaviria Correa of Colombia”).

Networkers SouthNorth and Pambazuka Press have released a provocative Festschrift (Experiments with Peace) to commemorate Johan Galtung’s 80th anniversary. The volume includes a chapter by CGNK founder and Governing Council Chair Glenn D. Paige exploring the nonkilling political leadership of Colombian Governor Guillermo Gaviria Correa (“Political Leadership, Nonviolence and Love: Governor Guillermo Gaviria Correa of Colombia”).

In April the Center for Global Nonkilling and Cascadia Publishing House released the English translation of Diary of a Kidnapped Colombian Governor, by Guillermo Gaviria, who was kidnapped and murdered by the FARC during a failed rescue attempt in May 5, 2003. The edition is launched on the seventh anniversary of his death and commemmorates Gaviria’s commitment to nonviolence as a political strategy.

Political Leadership, Nonviolence and Love: Governor Guillermo Gaviria Correa of Colombia

Introduction

Top-down political leadership is rarely the focus of attention in discussions of nonviolence and peace where emphasis is usually placed upon struggles of the dispossessed for justice from the bottom-up. At best leadership attention is accorded to eminent bottom-up figures such as Gandhi and King. With respect to top-down violent political leadership, the treatment is not the same. Leaders like Hitler, Stalin, and Mao are credited with enormous influence upon their societies and world affairs. Sometimes democratic leaders are credited with special contributions to violent successes, such as Abraham Lincoln in the American Civil War and Winston Churchill in WWII.

By contrast the top-down nonviolent leadership of Colombian Governor Guillermo Gavira presents us with something to ponder for its implications for future leadership for nonviolent global change.

The Governor

Governor Guillermo Gaviria Correa was born on November 27, 1962, in Medellín, capital of Antioquia, Colombia’s second most populous state. He was the eldest son of a family prominent in business, publishing, and politics. An engineering graduate of the Colorado School of Mines in the United States, he returned in 1985 to begin public service that included service as Antioquian secretary of mines and general director of the National Institute of Roads.

In 2000 he campaigned for a “New Antioquia” as Liberal Party candidate for governor. He was assisted by his wife Yolanda Pinto Afanador de Gaviria Correa, former secretary general of the National Institute of Roads. They had married on Colombia’s Independence Day, July 4, 2000. It was the second marriage for both; he with two sons, she with a daughter and three sons.

Elected governor by nearly 600,000 votes, 50.4% of the total and 200,000 more than his nearest competitor in a state of almost six million people, he launched a vigorous program of action. He first engaged more than 5,000 leaders in a process to identify Antioquia’s priority problems and to suggest solutions for them. This produced a Strategic Plan of Action and a Congruent Peace Plan. With Yolanda he traveled in caravans to various parts of the state to popularize and gain support for these plans.

He had diagnosed the root cause of Colombia’s decades of seemingly intractable violence to be the structural “imbalance” between the few rich and the many poor. Congruent with his Catholic faith, shared with Yolanda, he began to explore how to bring about nonviolent behavioral and structural change in Antioquia and Colombia by adapting the methods associated with Gandhi and King. This brought him into contact with Dr. Bernard LaFayette, Jr. and retired police Captain Charles L. Alphin, Sr., the world’s leading trainers in Kingian methods for nonviolent social change. They had been engaged in trainings for city officials, gangs, prisoners, taxi drivers, and others in Medellín.

To seek nonviolent knowledge the Governor and First Lady journeyed to the University of Rhode Island to participate in the 4th International Conference on Nonviolence, August 11-15, 2001, organized by its Center for Nonviolence and Peace Studies, directed by Dr. LaFayette. There they engaged in extensive discussions with participants, including several hours with Dr. N. Radhakrishnan, chair of the Indian Council of Gandhian Studies in New Delhi. Those who met the couple there saw they were deeply in love.

Back in Colombia the Governor continued to explore how the spirit and methods of nonviolence could help solve problems of state, paramilitary, revolutionary, and criminal bloodshed within the context of political, social, and economic structural inequity. During October 1-2 he organized a two-day nonviolence training workshop for himself and his cabinet led by Dr. LaFayette and Capt. Alphin. On November 22 he appointed a certified Kingian trainer Sr. Luis Javier Botero Arango to his staff as advisor in nonviolence (asesor en noviolencia). This was one of two pioneering appointments of nonviolence specialists to high government positions in that period. The other was the appointment of Thammasat University Muslim political scientist Dr. Chaiwat Satha-Anand as vice-president of the Strategic Nonviolence Committee of the National Research Council of Thailand.

March to Caicedo

In the spring of 2002, the people of the mountain coffee-growing town of Caicedo (pop. 7,000) called for government assistance against harassment by FARC guerrillas. The FARC had hijacked trucks carrying coffee to market, had assaulted a priest, damaged their church, and were threatening the peoples’ livelihood. They had declared themselves to be a nonviolent community.

Reminiscent of Gandhi’s Salt March and King’s March to Selma, the Governor planned a March of Reconciliation and Solidarity to Caicedo. The plan was debated in cabinet where some opposed it as too dangerous. So did the Governor’s father. But the Governor was convinced of the power and efficacy of nonviolence, even if he were sacrificed. He ordered that the police and army should not protect the March and should not attempt to rescue him if kidnapped or to retaliate if he were killed. His faith in nonviolence was unshakable.

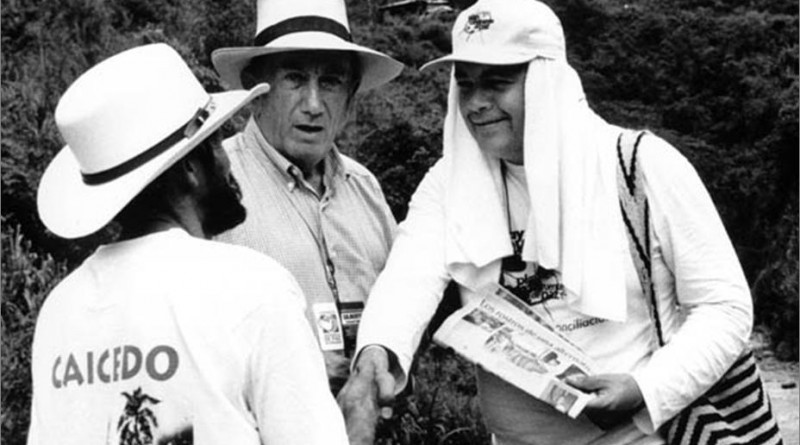

Led by the Governor and First Lady together with the Antioquian Peace Commissioner Dr. Guilberto Echeverri Mejía (former defense minister and Antioquia governor), and Catholic Father Carlos Yépez, one thousand marchers set forth from Medellín for the seventy-five mile March to Caicedo. Dr. LaFayette and IFOR vice-president Dr. Lou Ann Ha‘aheo Guanson from Hawai‘i accompanied them. The well-organized spirited March was enthusiastically welcomed by children to elderly in villages and towns along the way. White tee-shirted marchers were met by applause and fluttering white flags; at stops candies were tossed to children and the crowd. Like the songs of Gandhi’s movement and King’s We Shall Overcome it had its own poignant theme, a children’s song Padre Nuestro from the popular TV show Oki Doki. It was sung spontaneously at every opportunity and rest stop.

Padre Nuestro (Oki Doki)

Padre Nuestro dime quién puede

explicarle a los niños de aquí

tata violencia, tanta tristeza

que ya no hay donde jugar por ahí.

Our Father tell me who can explain

to the children here why

so much violence, so much sadness,

that there is nowhere to play.

Ending with the haunting last stanza calling for “amor.”

Padre Nuestro te lo pedimos

haz que en los hombres

renazca el amor.

Our Father we pray

that you revive in men

love.

At each of four overnight stops in towns along the way, the Governor and First Lady placed their footprints in concrete as mementos of the March. Despite a warning on the second day of FARC violence in the area and increased concern on the eve and morning of the last day discussed by him and his small group of associates, the Governor was determined to complete the March.

Kidnapped

On April 21, about three miles short of Caicedo, the FARC stopped the March. The FARC ordered that the Governor plus three others could advance. Yolanda wanted to accompany him but he ordered her to stay behind to take charge of the marchers. Then about 3:00 PM they embraced, knowing he might be kidnapped or killed, and he disappeared around the bend in the road accompanied by Peace Commissioner Mejía, Dr. LaFayette, and Father Yépez. At about 8:00 PM, Father Yépez returned with news that the Governor, Peace Commissioner, and Dr. LaFayette had been kidnapped. In the mountain dark and cold First Lady Yolanda led an anxious invocation for the blessing of the Virgin (Santa Maria, madre de Dios). Then apprehensive marchers boarded buses and returned to Medellín.

During April 23-26, First Lady Yolanda courageously chaired the 5th International Conference on Nonviolence. It engaged civic, diplomatic, and church leaders as well as Nobel Peace Laureate Mairead Maguire and Dr. LaFayette (released as an American by the FARC on April 22). More than 3,000 people participated. Remarkably for three days they did not clap hands as usual but adopted the silent Jain form of nonviolent applause. This substitutes raised arms and fluttering hands for clapping deemed to do violence to life-giving air. During the Conference Yolanda also led the First Nonviolence Children’s Camp with 1,300 children, aged 9 to 13, brought together from every social background and all parts of Colombia. Reached by helicopter it was held in a mountain Boy Scout camp in a guerrilla-active area.

In support of the Conference, Medellín was festooned with banners celebrating Nonviolence. Major newspapers, radio and TV stations carried special stories. Medellín, lamented as one of the world’s most homicidal cities in a country plagued by revolutionary, state, paramilitary, and criminal violence, became the world’s most nonviolence-awakened city.

Killed

On May 5, 2003, after 379 days in captivity, Governor Gaviria, Peace Commissioner Mejia, and eight of eleven kidnapped soldiers held with them, were killed in an unwanted, abortive, military rescue attempt undertaken by the Government of Alvaro Uribe. The rescue force, landed by helicopter 30 minutes distant from the camp, gave the FARC guerrillas time to kill their captives and escape into the jungle. Not a shot was fired between combatants. Another miscalculation was that the fierce FARC commander “Paisa” would be absent from the camp that day and that his young fighters would be too disorganized to resist effectively. But “Paisa” was there.

Thus the nonviolent Governor and companions became victims of two lethalities: readiness of the state to kill to rescue its own; readiness of revolutionaries to kill captives to prevent their liberation. This tragedy was preceded by a year of failed efforts to agree on a “humanitarian exchange” of prisoners by the Government and the FARC. In this effort First Lady Yolanda worked daily not only for the release of the Governor but for all of Colombia’s kidnapped.

In April the kidnapped and the guerrillas were playing volleyball; on May 5 only three of the kidnapped escaped being killed by them. One of the killers who participated and later left the FARC said he regretted what they had done.

Kidnap Diary

A Diary of entries addressed to Yolanda constitutes an inexhaustible legacy of insights into political leadership, nonviolence, love, faith, and the Colombian condition. It was published first in Spanish in 2005, Diario de un gobernado secuestrado, and next in English in 2010, Diary of a Kidnapped Colombian Governor. It will surely join the classics of world political prisoner literature and will reward reading by all who seek a nonviolent future world. It will inspire creativity in all the arts. It calls for a major biography and feature film like Attenborough’s Gandhi. The daily diaries were delivered to Yolanda in three batches. First by the FARC through the Office of the Public Defender of Antioquia on December 12, 2002 (113 letters). Second by the Army about a week after the rescue attempt (47 letters). Third, by the Attorney General’s office in May 2003 (43 letters). Additionally a Notebook with six entries was delivered to her in March 2005. Sixteen letters to Yolanda, his brother Anibal who was to succeed him a Governor, his mother, father, and others were also delivered to her.

In the Diary Guillermo conveys to Yolanda details of kidnapped jungle life; relations with guerrilla fighters and fellow captives; food, health, shelter, and coping with disease. They moved hastily from camp to camp on little notice, by mule, horse, or on foot to places named by him and Gilberto with creativity and humor such as “Villa Nonviolence,” “Gnatville,” “Villa Sadness,” “Crab Louse Villa,” “Cockroach Residence,” and “Swampville.” When hopeful of prisoner exchange one camp was called “Villa Waiting.” Guillermo and Gilberto were treated well by the guerrillas, although he appeared haggard and bearded, showing lost weight in a video made to demonstrate the captives were alive to their families.

Guillermo and Gilberto benefited from the long captive experience of eleven fellow military prisoners with whom they worked in setting up camps and various projects. With dates of detention in June 2002 they were:

Lieutenant Alejandro Ledesma Ortis, two years, six months

Lieutenant Wagner Tapias Torres, five years

Sergeant Pedro J. Guarnizo, five years

Sergeant Hector Lucuara S., three years, ten months

Sergeant Heriberto Aranguren, ten years

Sergeant Francisco Manuel Negrete, three years, ten months

Sergeant Yercino Navarrete, three years, ten months

Sergeant Samuel Ernesto Cote C., four years

Corporal Agenor E. Viellard, two years, six months

Corporal Mario Alberto Marín, three years, ten months

Corporal José Gregorio Peña, two years, six months

Sergeants Aranguren and Navarrete were assigned to help Guillermo and Gilberto. When the May 5, 2003 massacre came, only Guarnizo, Aranguren, and Viellard survived.

Relations with FARC captors were generally good. Rations were shared when short or varied when abundant. Concessions were made to assist movements in view of age and health. On March 23, he was planning to begin English classes for the guerrillas (male and female). For Guillermo, avid learner, the jungle, trees, plants, fruits, rivers, insects, snakes, became a school for advanced study. He was keen to apply new knowledge to improve rural life. How to improve Colombian agriculture for benefit of farmers is a recurrent theme. On the other hand Nature inspires and occasionally provides an opportunity for a favorite pastime of fishing in nearby streams when permitted by the guards, even once allowed alone.

Heavy rains were frequent in many diaries, but when the sun breaks out, the glory of the sky, clouds, trees, and mountains—combined with intense love for Yolanda—breaks through moods of “melancholy,” “sadness,” and “uncertainty” to proceed with Faith.

Communication

Although the kidnap camp was frequently moved, it was not completely out of contact with the relatives of the kidnapped and events in Antioquia, Colombia, and the world. The Red Cross through the FARC occasionally sent care packages to the soldiers with clothes, medicines, books, and other treats. Guillermo and Gilberto were able to receive similar things sent by Yolanda and Gilberto’s wife, Martha Inés, through the same channel. By radios sent by Yolanda the kidnapped were able eagerly to listen to broadcasts such as The Voices of the Kidnapping and How Medellín Woke Up in which relatives sent messages to them. At one point even TV and films could be viewed. News of efforts by Yolanda and others in Colombia and abroad (e.g., UN, EU, Vatican, and Cuba) to secure a “humanitarian exchange” of the kidnapped and rebel prisoners was followed with daily swings of optimism and pessimism. Guillermo was keen to follow and critique national and state politics. As Governor, some cabinet secretaries reported to him on their work by radio. He criticized kidnappings, attacks, and killings by the FARC and the other groups. He saw them as strengthening hostile military and public opinion. He also criticized hostility fanned by government figures and media commentators. He preferred a mass nonviolent movement to end the killing and kidnapping.

Political Leadership and Nonviolence

From the day of his capture the Governor sought to reach the top FARC leadership with his proposals for nonviolent reconciliation and structural change. He wanted to engage them to consider the idea of Antioquia as a “Laboratory of Nonviolence.” Although able to reach the local commanders and to obtain general respect for his sincerity, top level contact and dialogue was never achieved. As the diaries show, although there was no assurance of his advice being delivered, Guillermo continued as Governor to show concern for the success for all aspects of Antioquia state administration. By radio he received reports from secretaries upon their work, entering diary comments upon them as well as upon other state, national, and international affairs.

Over his year in captivity Guillermo deepened and elaborated his initial conviction that the faith- and pragmatic-based theory and practice of nonviolence offered the best approach to solving Colombia’s problems of violence and poverty. Before the March to Caicedo he had declared “Nonviolence was born with Jesus Christ; in the 20th century it was carried forward by Gandhi and King; and in the 21st century it will be the guiding light of the people of Antioquia.” He wrote, “I have concluded that without nonviolence no democracy can exist” (August 1). He envisioned nonviolence as a shared ethic permeating all sections of Antioquia’s people achieved in part by courses in nonviolence throughout the state’s educational institutions. He continued to study nonviolence, requesting books on nonviolence such as those by Gandhi, King, and Gene Sharp. He showed he had been studying topics like nonviolent social offense as well as books on Napoleon, Bolivar, and Colombian military history. People should know that nonviolence involves not “religious fanaticisms” but “humanitarian and political science” (April 21).

As leaders learn, they teach and learn more. One Sunday, August 11, he wrote to Yolanda: “Love I have been very diligent in preparing a talk on nonviolence, and now I have it more or less structured. Really this is my first theoretical evaluation of the topic of nonviolence. Let’s see what the reaction of the military officers and Gilberto is.” The next day he reported “complete success” but he would have to divide it into two parts. His hour and a half presentation had produced two hours of discussion. It took two more days to finish. Earlier he had been teaching English to the kidnapped and later to the guards.

In March–April 2003, shortly before his May 5 murder, Guillermo increasingly thinks about proposals to promote nonviolent change in Antioquia, Colombia, and the world. He is realistic about problems to be solved. “Leading signifies constructing solutions, and if it is nonviolent leadership it is very probable that this is more difficult and requires more creativity and valor when putting them into practice” (April 13). He reports new interest in “shared leadership” defined as “the collective product of the nonviolent empowerment of the people of Antioquia” (April 9).

He envisions the UN as a “world organization of nonviolence” (March 3). Earlier on August 8, 2002, he had proposed to establish a Global Center for Nonviolence in Medellín “to strengthen bonds with nonviolent entities in other parts of the world and to explore the study of this literature which is more abundant and serious than I had first thought.” At the national level he advocates a Minister of Nonviolence, but not “of peace” (April 23). He has studied nonviolent defense and plans a “proposal to the Colombian people to transform our armed forces into civil corps of peace or nonviolent brigades. An army without guns” (March 22). In Antioquia he envisions a wide range of public and private sector institutions and structural changes necessary to achieve a nonviolent culture. This includes “a new role that the armed forces and the police should play in a nonviolent society along with transforming the approaches to punishment and rehabilitation that the society presently uses” (April 22). He considers creation of a Secretariat of Nonviolence to collect comprehensive statistics on violence and to work with other agencies such as the Secretary of Education to promote a culture of nonviolence through publications and study of the history of nonviolence in Colombia (April 23). He advocates courses for nonviolence in universities and large scale expansion of children’s camps for nonviolence.

His proposals and recommendations reveal a leader creatively thinking about how nonviolent institutions and programs could contribute to behavioral and structural change to remove injustices as both causes and products of violence between rebels and the state.

Love and Faith

Throughout his captivity—amidst the uncertainties of physical existence and prospects for release—Guillermo expressed and was sustained by powerful love for Yolanda and his Catholic faith. A key word count of the Diary will surely show “love” as its heart with “nonviolence” and empathic concern for the well-being of others as close companions. Each of his 203 diary entries begins and ends with varied expressions of passionate and respectful affection compounded by shared religious faith that convey a profound sense of “soul mates.” “Amor mia” (my love), “Dulce amor mia” (my sweet love), “Mi vida” (my life), “Dulce princesa mia” (my sweet princess). “Amor” appears frequently inside the entries. The diaries speak of his strong desire to create new life out of their love, a daughter to be named “Yolandita.” Love is expressed to their present children, to his mother, father, and to other members of their families.

On Yolanda’s part, radio reports of her love for him, her work with others for humanitarian prisoner exchange, and her work for carrying out his projects in Antioquia uplifted his spirits out of “melancholy” and “sadness,” filling him with hope and pride for a “special wife,” as fellow prisoners praised her devoted service. Along with the Gospel he read and re-read the single batch of her letters that were delivered to him.

Conclusion

Governor Gaviria’s nonviolent leadership demonstrates implicit understanding of Aristotle’s ancient explanation of revolution’s roots in ruler reluctance to live in conditions of equality with the ruled (Aristotle 1962); Burton’s thesis that neither moral suasion nor coercion will end violence without engagement in processes of problem-solving that respond to human needs (Burton 1979); Heifitz and Linsky’s thesis that broadly “adaptive” versus narrowly “technical” approaches to problem-solving in crisis promise greater success (Heifitz & Linsky 2002); and Galtung’s comprehensive approach to peaceful social transformation through deep-rooted cultural, structural, and behavioral change achieved through transcendent creativity (Galtung 2004).

Guillermo’s experience and that of nonviolent Petra Kelly’s party and parliamentary leadership (Kelly [1992] 2009) call for study by future nonviolent political leaders and their followers. Their top-down lessons need to be combined with those from bottom-up nonviolent leadership and mass action experiences powerfully theorized by Gene Sharp (1973). The study and practice of nonviolent political leadership offer hope for progress toward a peaceful, free, and just human future in which—“Everyone has the right not to be killed and the responsibility not to kill others” (Nobel Peace Laureates 2007, Principle 13).

As the slogan of the March to Caicedo reminds us: “Si…Hay un Camino—la Noviolencia.” “Yes…There is a Way—Nonviolence.”

Bibliography

- Aristotle. The Politics. Book V, Chapter 4. Translated by T.A. Sinclair. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1962.

- Burton, John. Deviance, Terrorism & War: The Process of Solving Unsolved Social and Political Problems. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1979.

- Galtung, Johan. “Violence, Peace and Peace Research.” Journal of Peace Research, 6 (1969), 167-91.

- — Transcend & Transform: An Introduction to Conflict Work. Boulder, Colo.: Paradigm Publishers, 2004.

- — “The TRANSCEND Approach to Simple Conflicts.” In Glenn D. Paige and Joám Evans Pim, eds. Global Nonkilling Leadership: First Forum Proceedings. Honolulu: Center for Global Nonkilling, 2008.

- Gaviria Correa, Guillermo. Diario de un gobernador secuestrado. Bogotá: Revista Número Ediciones, 2005.

- — Edited by James F.S. Amstutz. Translated by Hugo Zorilla and Norma Zorilla. Diary of a Kidnapped Colombian Governor: A Journey Toward Nonviolent Transformation. Telford, Penn.: DreamSeeker Books, 2010. Copublished with Herald Press and Center for Global Nonkilling.

- Heifetz, Ronald A. and Marty Linsky. Leadership on the Line: Staying Alive Through the Dangers of Leading. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2002.

- Kelly, Petra K. Nonviolence Speaks to Power. Edited by Glenn D. Paige and Sarah Gilliatt. Honolulu: Center for Global Nonkilling, [1992] 2009.

- Nazareth, Pascal Alan. Gandhi’s Outstanding Leadership. 3d ed. Bangalore: Sarvodaya International Trust, 2010.

- Nobel Peace Laureates. Charter for a World Without Violence. Rome: Nobel Peace Laureates, 2007.

- Padre Nuestro (Oki Doki). YouTube.com.

- Paige, Glenn D. The Scientific Study of Political Leadership. New York: The Free Press, 1977.

- — Nonkilling Global Political Science. 3d ed. Honolulu: Center for Global Nonkilling, 2009.

- Sharp, Gene. The Politics of Nonviolent Action. Boston: Porter Sargent, 1973.