Facing up to the Charlie Hebdo tragedy, by Jean-Marie Muller

On the afternoon of January 7, having heard that an attack had been carried out in the premises of French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo, I found out on the internet that Cabu figured among the journalists killed. This piece of news deeply moved me. I had come across him on several occasions during my life as an activist, and we had developed a certain friendship. The smile that lit his face expressed great serenity. He showed great gentleness. I looked forward to seeing his cartoons every week as I opened Le Canard Enchaîné [another French weekly satirical newspaper].

I read the names of the other people killed in the attack – journalists and police – and gauged the extent of the tragedy that had hit the whole of France. These horrible murders are the negation and the denial of the humanist values that are the basis of civilization. On Sunday January 11, I marched the streets of Paris alongside hundreds of thousands of other French people, demonstrating our determination to refuse all forms of fear of terrorist threats and to continue to fight for freedom. This impressive popular mobilization could be a sign of hope for French democracy. The key idea around which those thousands of French people chose to gather was to assert their will to form a community beyond any form of cultural isolationism, and to experience true secularism, one that respects everyone’s convictions and asserts universal ethics, which alone can be the basis for equality, liberty and fraternity..

The publication of the Muhammad cartoons in question

Nonetheless, I must admit that I cannot give my full support to the decisions made by Charlie Hebdo concerning the publication of the cartoons of the Prophet Muhammad.

As it happens, I was in Jerusalem from February 2 to 13 2006. I had been invited to go to Gaza by Ziad Medoukh, a French lecturer at the Al-Aqsa University in Gaza in order to run a training session on nonviolence. During a previous stay in Israel, the French Consul had assured me that he would give me the green light to go to Gaza. But this time, he let me know that because of the publication of the Danish cartoons in France (France-Soir had published them on February 1 and they were to be published on February 8 in Charlie Hebdo) and the hostile reactions that they had caused among Arab people, my trip to Gaza was out of the question. On February 2, the Al-Aqsa martyrs brigade had stated: “All Norwegian, Danish or French citizens in our country are targets.”

I therefore received the news concerning the publication of the cartoons of Muhammad in France, in rather peculiar circumstances, while actually in the Middle East. Seeing things from the outside undoubtedly led me to a slightly different perception of reality to that which seemed to prevail in the West. As soon as I returned to France I wrote an article entitled “The clash of the cartoons”. Here are a few extracts from this article:

“If we simply look upon the events caused by these cartoons – first published in Denmark – through the distorting lens of Western secular ideology, we strongly risk viewing these publications as the mere legitimate exercise of freedom of speech. We then become unable to understand how Muslims interpret those same events. In a democracy, freedom of speech is an imprescriptible right, but not an absolute right. It finds its limits in respect for others. It is only legitimate when it is combined with intelligence and responsibility, two virtues that are also the basis for democracy. The rhetoric surrounding freedom of defamation that claims to justify the publication of these cartoons presents Muslims with a caricature of Western democracy. From then on, all those within the Muslim world who fight for the values and principles of democratic secularism find themselves in an unbearable position.”

“When we consider the deficit of freedom of speech in a number of societies – notably in countries ruled by regimes that refer to Islam – it becomes easier to gauge the decisive value of this freedom in order to build an authentic democracy. It is the responsibility of those who are lucky enough to benefit from it not to discredit it with unreasonable abuse. (…)

“Any religion certainly ought to be rationally criticized, and above all concerning its take on violence. This demanding debate is not easy, but one of the gravest consequences of the publication of these cartoons is that it is made even more difficult. (…)

“Unaware of their arrogance, Westerners call on Muslims to show humour in the face of the insolence of these cartoons that are meant to be humorous. But humour is too precious a good to be overworked. It disowns itself when it turns into mockery and stigmatization. In reality these cartoons are nothing but a caricature of humour.

“There was no need to be psychic to foresee that such satires ridiculing the Prophet Muhammad would be perceived by Muslims as an offence to their religion. For all that, these crowds of angry Muslims, manipulated by political groups or regimes and uttering cries of hatred against the West, sometimes even crying out for murder, definitely give a grotesque image of Islam.

“The worst of it all is that this clash of the cartoons has taken us a step forward towards the hateful logic of the “clash of civilizations”. The relations between the West and the Muslim world embody a considerable challenge. In order to take up this challenge, it is necessary to boldly clear the path to an uncompromising dialogue which would allow us to invent a common future, beyond past transgressions and in view of common ethical references.”

These judgements may appear harsh to some, too harsh. I would like to point out that they were written in 2006 and that they concern the Danish cartoons published in France. We have probably forgotten the passions they then sparked within Muslim communities in France and throughout the world. As for the cartoons published by Charlie Hebdo since then, certain reservations ought to be expressed. These drawings all differ from each other and each must be considered individually from a number of perspectives.

Religions, unfortunately, ignore nonviolence

Following the tragedy of January 7 and 8, religious leaders have been anxious to condemn these murders, stating that religions only preach tolerance and peace and that they had nothing to do with this tragedy. But this religiously correct language may contain a denial of reality.

The history of humanity is a history of crimes. Hopelessly so. Murderous violence inevitably seems to weigh on history. The universal requirement of rational conscience forbids murder: “Thou shalt not kill”. However, our societies are ruled by the ideology of necessary, legitimate and honourable violence which justifies murder. From then on, for numerous reasons, Man becomes the killer of other Men. And religion often emerges as being an integral part of the criminal tragedies that bring bloodshed to the world.

Even when they do not kill “in the name of religion”, human beings repeatedly invoke religion while killing. In many circumstances, religion allows murderers to justify their misdeeds. It offers them a doctrine of legitimate violence and righteous killing. On many occasions, it wrongly leads murderers to believe that “God is on their side”.

Remarkably, despite emphasis being placed on different points, religions tend to follow the same doctrine. What matters most is not what religions say about God, but what they say about Man, and more specifically what they do and do not tell Man.

Taking Gandhi literally

Gandhi definitely ought to be taken literally when he maintains that nonviolence is the truth of the humanity of Man. Gandhi also claims: “God can be attained only through nonviolence.” By ignoring nonviolence, religions have misunderstood God whose being – in theory – is free of violence. The opposite of faith is not unbelief, but violence. But what is graver still is that in ignoring nonviolence, religions have misunderstood Man, whose spiritual being finds fulfilment in nonviolence. In justifying violence, religions have betrayed Man. They deny the humanity of Man.

The radical opposition between love and violence

Religions have often been criticised for their justification of violence. Admittedly religions are guilty of contributing to violence, but above all of not contributing to nonviolence. This means it is not enough for religions to stop justifying violence; they have to stop ignoring nonviolence.

Even when they have preached love, religions have not dared to highlight the implacable contradiction, the essential incompatibility, the absolute antagonism, the radical antinomy between love and violence. They have even let Man believe that it was possible to combine love and violence into one single rhetoric. Here lies the crucial mistake. For in this rhetoric, the principle of nonviolence dissolves. The transcendency of Man is to fear murder more than death.

Religious doctrines justify murder

Numerous voices have claimed loud and clear that “Islamism has nothing to do with Islam”. Admittedly, it is necessary to avoid any “confusion”, to close the door on the stigmatization of Muslims, considered to be co-responsible for Islamism and its criminal drifts. Islamophobia must be challenged uncompromisingly and condemned. However, the possibility for Islamists to resort to a number of Koranic verses in order to justify their fundamentalist conception of Islam – beyond the compromises of principle in history – cannot be denied. Muslim law rigorously calls for extreme severity towards those who criticize the prophet. Islamic law does not exclude the killing of blasphemers in any way. Muhammad himself did not hesitate to have dissidents who had challenged his authority killed. Islamists can claim to be consistent, radical and therefore uncompromisingly Orthodox. Links can be established between traditional Islam and the Islamism of fundamentalists as soon as the Koran allows the fundamentalist interpretation that Islamists make of it.

As soon as such criticism of Islam is launched, the same can be said of any religion. In any event, this statement is a confirmation, and not an invalidation. The preceding analysis of the Koran can undoubtedly apply to the Bible where many verses justify violence. The compromises of principle of both Judaism and Christianity with violence have varied a great deal throughout history according to the time and place. Jesus challenged the law of retaliation; he asked his friends to put their swords back in their sheath and not to fight evil with evil. Nevertheless, this did not prevent the Inquisition from being Catholic before it became Muslim, and the Christian wars of the XVIth century – “Think only of the night of Saint Bartholomew” – were quite as bad as Muslim wars today.

Necessity does not equal legitimacy

Admittedly, we know that absolute nonviolence is impossible in this world. Man can become the prisoner of the harsh law of necessity which forces him to resort to violence. But even when violence seems necessary, the requirement of nonviolence remains; the necessity of violence does not put an end to the obligation of nonviolence. Necessity does not equal legitimacy. Justifying violence under the pretext of necessity would make violence absolutely necessary and lock the future into the necessity of violence.

In striking compromises with murder, religions have not committed any offences, they have made errors, errors of doctrine, errors of thought, which are all errors against the mind. Today as yesterday, it is a categorical moral imperative for religions to decide to break once and for all with their doctrines of legitimate violence and righteous killing, and resolutely to opt for nonviolence. The future of humanity largely depends on religions making such a decision.

Hope lies in the fact that the extreme nature of the fundamentalist violence committed in France, but also in a number of countries throughout the world, in the name of religion, may force religious leaders to break with violence.

Fighting antisemitism

The murder of four French Jewish people on January 8 in Porte de Vincennes in a Hyper Casher kosher supermarket has added tragedy to the drama of the deaths of the Charlie Hebdo journalists. Here again, any trace of anti-Semitism must be absolutely condemned. But we must recognize that this anti-Semitism is partly provoked by the policy which the State of Israel has been exercising in the name of radical Judaism. There is a real risk of the condemnation of anti-Semitic racism suggesting a justification of the policy of the Israeli government. From that point of view, the presence of the Israeli leader at the demonstration on January 11 was not devoid of ambiguity. Who could claim that the rights of Palestinian people are respected by the state of Israel?

France is at war

“France is at war against terrorism”, declared the Prime Minister, Manuel Valls, on January 13 in the French National Assembly. Admittedly, the “terrorist” threats that hang over France are real enough, but it would be an illusion to believe that security measures alone, that is to say police and military measures, could contain and eliminate them.

Speaking about horror, barbarity and monstrosity alone may well mislead us away from the political nature of these acts. In order to understand terrorism, it is not enough to point out its intrinsic immorality. As soon as the political nature of terrorism is acknowledged, it will be possible to look for the political solution it requires. The most efficient way to fight terrorism is to deprive its authors of the political and economic reasons they invoke to justify it. That is how it will be possible to weaken the popular basis which terrorism needs most. Terrorism often takes root in a soil fertilized by injustice, humiliation, frustration, misery and despair. The only way to make terrorist acts stop is to deprive their authors of the political reasons invoked to justify them. From then on, terrorism cannot be overcome by war, but by justice. Here and there.

One last reflection which again may seem improper; the Charlie Hebdo tragedy did not claim 17 but 20 victims. The three killers, young French people, born in France but whose lives were in default, are also victims of terrorism. Whatever the horror of their terrible criminal acts, they were also Men. Beyond death, their humanity must be restored. We will then be able to mourn the deaths of these three men, with the respect they deserve as people/human beings.

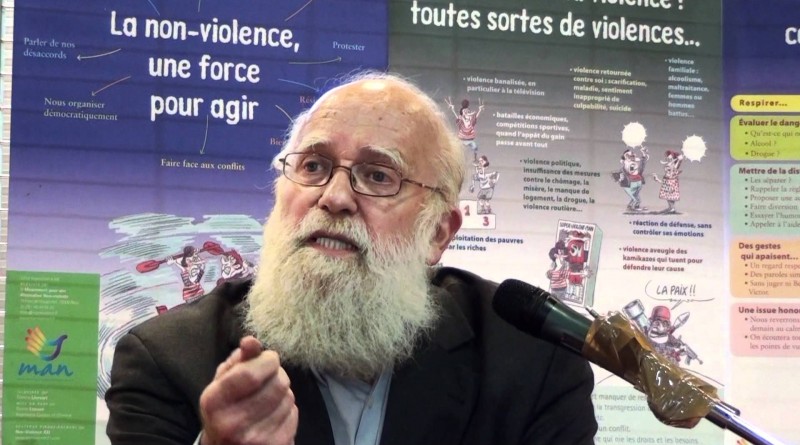

* Jean-Marie Muller is a Philosopher and writer. Author of The Principle of Nonviolence: A Philosophical Path and Désarmer les dieux, Le christianisme et l’islam au regard de l’exigence de non-violence, Le Relié Poche, 2010. Member-founder of the Mouvement pour une Alternative Non-violence (MAN) (Movement for a Nonviolent Alternative) Winner of the 2013 International Award of the Indian Foundation Jmanalal Bajaj for the promotion of Gandhian values.

Translated by Rebecca James