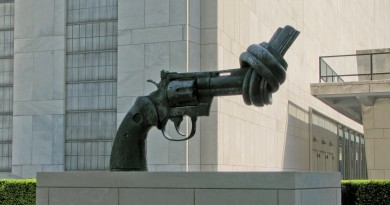

CGNK at the Biennial Panel on the death penalty

Every two years, the Human Rights Council holds a special thematic debate on the death penalty.

International Law, when it permits it, allows such a fate only for “most serious crimes” (Article 6, 2 of the Covenant on civil and political rights). This was this year’s theme.

As the council does not take decisions on such occasions, the legal definition and limits of what is a most serious crime are only reminded, though it may help positions to evolve.

Mister Volker Türk, High commissioner for human rights, recalled the bases of the situation, the low deterrent effect but also that as long the penalty exists, dignity would not be fulfilled. He called for weaving a new fabric of dignity.

Mister Idrissa Sow, member of one of the bodies of the African Commission of Human and Peoples Rights presented the situation in Africa, where death penalty is receding.

Ms. Azalina Othman Said, Minister of Justice of Malaysia explained that though the country is abolitionist in practice, it has made the legal change towards “most serious crimes only”, eliminating from its penal code issues that do not imply an intentional killing and all mandatory death penalties sentences. Noteworthy, this was done not only to match international standards, but also to forward the change of opinion in the population, believed to be in favor of the penalty.

Ms. Mai Sato, Japanese scholar, on the public opinion issue explained that too often polls regarding the death penalty are one-sided as they do not consider what the public opinion would be if Governments would take the lead for the abolition. She also added very interesting usually unknown statistics on death penalty and explained how moving, as a young scholar, from Japan, where there is a rather tolerant popular opinion about the penalty to live in abolitionist countries brought her to a new perspective as she saw the difference about how life is valued there. Conversely, she said that death penalty is an expression of lethal control of populations.

Mr. José Manuel Santos Pais, Member of the Human Rights Committee recalled, with a very kind approach, where the law stands and how the Committee applies it.

Finally on the panel, Ms. Belal explained how Pakistan interrupted its moratorium in 2014, executed 516 persons for terrorism until 2019 and then reestablished the moratorium, limiting the law to most serious crimes. What was deeply moving in her presentation is that this change of law and policy was made possible through a strong civil society advocacy at all levels, including in courts, but also by largely using the United Nations mechanisms, complaints, appeals and reporting. She also mentioned that afterwards, there was no backlash in public opinion calling for reinstatement.

30 states and 6 NGO were then given the floor. Some highlights: All Portuguese speaking countries have abolished it. 30,000 persons are presently standing on death rows. A vivid call was made against Iran for executing protesters. Other calls were made for not executing people simply because it may seem cheaper to kill them than to keep them lifelong behind bars; not to kill them for witchcraft and to support NGO’s doing work on the topic. Numerous appeals were also made for more transparency.

Retentionist States defended themselves, sometimes quoting the General Assembly resolution calling for a moratorium, using the self-determination clause set therein or saying they were limiting themselves to most serious crimes.

Civil society denounced the fact that most often death penalty is used for political purposes, against drug offenders, minorities, and marginalized persons and in some situations permitting the death penalty too easily leads to extrajudicial killings.

Your Center for Global Nonkilling, your representative Christophe Barbey, first said in a rhetoric sense said that any killing is a most serious crime. Then he insisted on the fact that there is no right to kill whatsoever, which would go against the very purpose of law, that is to sustain life for all and peaceful relations by all. He then gave details on when law sometimes nevertheless permits killing: self-defense, though a failure of prevention and nonviolence, of proportionality; humanitarian law – it seems humanitarian conference could be underway – and death penalty. He highlighted that the value the life of our human species requires showing that we care for life, universally. He also called for a debate on public opinion in favor of the abolition.

Little propositions were made for further work, but at least the following possibility appears to us. A comprehensive list of the status of all States regarding the life constitution will allow for cross reading and analysis. Ratifying the genocide convention, the Covenant on civil and political rights which protects the right to life and abolishing the death penalty (including for most serious crimes) will show for which States the greatest work is needed to achieve universal protection of the right to life.

With your participation, we carry on!

Video of the whole panel here (the 2 first hours).

CGNK’s intervention is here (1h15.35). At the end of the statement see the smile of the person behind the President.

Our full declaration in English and French is hereafter.

Mister President,

Dear Dignitaries and Excellencies,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

Good morning,

In a philosophical perspective, guided by the Nonkilling principle and the right to life, any killing is a most serious crime.

It is not a matter of words: they are lives at stake, so many of them; whoever they are, whatever they did, they are potentially beautiful lives.

We do not recognize any right to kill. Killing is always a wrong.

Sometimes law has granted three powers (not rights) to kill.

Which goes against the noble goal of law: that is to sustain life for all, and peaceful relations by all.

These legal powers to kill have sometimes been granted for:

1) Self-defense. Though if it results in a killing, it is most likely a failure of prevention, of nonviolence and disproportionate.

2) Granted for humanitarian law. My country, Switzerland, has suggested last Friday at the Security Council a new humanitarian conference: for the right to life, this must happen.

3) And there is the power to kill granted for death penalty.

At a time in which we, all of us, you and me and all our institutions, States, we must learn and strive not to kill our own species, which would be the final most serious crime, abolishing the death penalty is one of the necessary steps showing that we –

universally – we care for life.

I have a question for the panelists, for the States still in the practice: How can we help you to see the beauty and the value of life, of its perpetuation ? Help you from committing the most serious crime of killing anyone?

As I have a few seconds left, I have a wish: May our panel in two years speak about populations in favor of the abolition [and the duty of exemplarity of States].

May we all have a good life.

Thank you, Mister President.

Chers êtres humains,

Monsieur le Président,

Dignitaires et Excellences,

Mesdames et Messieurs,

Bon après-midi,

Dans une perspective philosophique, guidés par le principe de non-meurtre et le droit à la vie, tout meurtre est un crime des plus graves.

Ce n’est pas qu’une question de mots : Des vies sont en cause, elles sont si nombreuses, qui qu’elles soient ou quoi qu’elles aient faits, toutes ces personnes peuvent mener des vies magnifiques.

Nous ne reconnaissons aucun droit de tuer. Tuer est toujours un tort, on non-droit. La loi a parfois accordé des pouvoirs (non pas des droits) pour tuer.

Cela va à l’encontre du noble objectif de la loi : celui d’assurer la vie pour toutes et tous, et celui de créer des relations pacifiques entre toutes et tous.

Ces pouvoirs pour tuer ont parfois été accordés pour :

1) La légitime défense. Mais s’il en résulte un décès, il s’agit probablement d’un échec de la prévention, de la non-violence et un acte disproportionné.

2) Accordé par le droit humanitaire. Mon pays, la Suisse, a proposé vendredi dernier au Conseil de sécurité une nouvelle conférence humanitaire : Pour le droit à la vie, elle doit avoir lieu.

3) Et il y a le pouvoir de tuer de la peine de mort.

A l’heure où nous toutes et tous, vous et moi et toutes nos institutions, les États, nous devons apprendre et nous efforcer de ne pas tuer notre propre espèce, ce qui serait l’ultime crime le plus grave, l’abolition de la peine de mort est l’un des étapes nécessaires montrant que nous – universellement – nous prenons soin de la vie.

J’ai une question pour les panélistes, et pour les États qui pratique encore : comment pouvons-nous vous aider à voir la beauté et la valeur de la vie, de sa perpétuation ? Et comment vous aider à ne pas commettre le crime le plus grave, tuer qui que ce soit ?

Puisqu’il me reste quelques secondes, je souhaite voir, comme thème pour notre prochain panel dans deux ans, les populations souhaitant l’abolition de la peine de mort [et le devoir d’exemplarité des États].

Que toutes nos vies soient belles.

Thank you mister President.